The Female Abject in Malayalam Horror Films

(Niyas S.M., Research Scholar, Institute of English, University of Kerala)

The notion of the ‘abject’ is defined by Julia Kristeva as that which disturbs identity, system, order, and does not respect borders, positions and rules. The abject also collapses the borders between natural and supernatural, human and non-human, normal and abnormal, the clean well-formed and proper and the dirty or deformed body. An apposite example of the abject is the portrayal of women as ghosts in Malayalam Horror films. What is conspicuous in this discourse of the abject is its politics of representation in which women, in the form of ghosts, are visualized as abjects, physically and psychically, and it paves way for the male-folk to subdue the female resorting to the ideological apparatuses of patriarchal power.

The present paper attempts to analyze how the female ghosts in Malayalam films, though they collapse the system and order as a kristevian abject, are finally cajoled to fall in line with the mythifying process of the patriarchal ideology, through the phenomena of exorcism which is symbolic of immasculation or internalization of male power and ideology to disempower the revolting female body or entity, and nailing into the tree, a powerful signifier in ghost films implying the penetration of the phallus into the female body, and thus the perturbed male power is reinforced, and it is intertwined with a story that gradually becomes a myth. Thus, the patriarchal success is drummed, and the dominant ideology is safe once again.

The present paper attempts to analyze how the female ghosts in Malayalam films, though they collapse the system and order as a kristevian abject, are finally cajoled to fall in line with the mythifying process of the patriarchal ideology, through the phenomena of exorcism which is symbolic of immasculation or internalization of male power and ideology to disempower the revolting female body or entity, and nailing into the tree, a powerful signifier in ghost films implying the penetration of the phallus into the female body, and thus the perturbed male power is reinforced, and it is intertwined with a story that gradually becomes a myth. Thus, the patriarchal success is drummed, and the dominant ideology is safe once again.

For the purpose of substantiating the argument, I would like to take up mainly two films Manichithrathazhu (It is purely a ghost film while taking off the Psychological elements) and Akashaganga. One thing pivotal in these ghost films is the hidden and repressed fear that is experienced by the dominant class. It is the haunting guilt consciousness in the collective unconscious of the male psyche that is materialized in the form of ghosts. And again in these stories, the ghost or the abjectified woman, most probably an eternal feminine, might have been victimized by the male power, and this stirs her soul to reincarnate as a female fatala, but only to be tamed and finally mythified in a lonely castle or a tree, evoking nightmares in the minds of the oppressors. Thus, the revolting female body that is reckoned as ‘defiled,’ is purified. And the male-folk regard it to be their duty to ‘purify’ or ‘normalize’ the female abject. Analysing the film Akashaganga, the dominant class, represented by the Manikyasseri family is always in fear of the ghost of Ganga, a maid who had been burnt to death, because she was in love with a member of the family. Since then, the ghost of Ganga started avenging, and she has become a frightful image to each member of the elite group. The transformation from the eternal feminine to the female abject is occurred. Here, woman, represented as the female abject, is a perennial fear to the community. The male community cannot revel in sexual pleasures and living as celibates. But, the dominant ideology, as usual, is capable of burying all the fears emanating from the subaltern through exorcism, and by nailing the ghost into the tree. Thus, all the mail power is focused on the nail or the symbolic phallus, and it perforates and subdues the rejuvenation of the subaltern imaginary. Hence, the abjectified female body, the cause of fear to the male psyche, is nullified by the nail that converges all the male power to a point. Thus, women become only a concept or an abjectified object to be subdued by the male power.

And the pattern of the ghost film is also the rejuvenation of this subdued woman and her final confinement, and the subsequent freedom and release from fear by the dominant ideology. In Manichithrathazhu and Akashaganga, there is a fear of the subdued female that has been traditionally inscribed into the collective unconscious of the patriarchal set up. This fear always hovers over the films, trammeling to bestow on a positive image to the leading women characters. They are the abjects, the evil ghosts, the Semiotic urges, needed to be removed from the Symbolic. The ghost-haunted woman is also depicted as a monstrous feminine who would coax, hoax and castrate men.

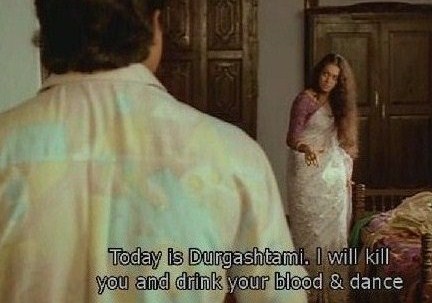

As has been designated, it is the duty of the male community to tame the ghost or abjectified woman, and thus, bring order into the disordered body of society. Hence, many of the ghost films bear images of male domination over the female body as a tactic of female subjugation. In the film Akashaganga, the body of Ganga and Maya are burnt though Maya is salvaged when the dominant ideology feels that she is unfettered of the influences of the ghost of Ganga. In Manichithrathazhu, Ganga, haunted by the ghost of Nagavalli, is beaten black and blue by the ‘purifier’, and thus, the male community is released of its own repressed fear. It is also to be noted that women, delineated as ghosts in films, come from subaltern or culturally low family who molest the elite, but they are thwarted by the elite towards the end. As a retort, ghosts evoke extraordinary fear, and break the dominance of the male body language, and employs violence at the non-performative and passive male body (passive before the ghost). Thus ghost films also become a female domination over the traditionally mythified male body. Sucking the blood of the dominant body, as seen in the film Indriyam, ghosts are distended, though the same ideology crushes them.

In order to evoke fear and loathe, ghosts are simulated and abjectified. This abject is what Bakhtin terms as ‘grotesque’ in which a bodily part comes to be too expressive. Eyes which bulge are grotesque, because the grotesque is looking for that which protrudes from the body, all that seek to go out beyond the body’s confines. Hence, ghosts are women who are grotesque creatures whose bodies transcend our preconceived notions of the female body. It is obvious in films like Meghasandesham and Sreekrishnaparunthu, in which ghosts appear as most grotesque with pointed fangs and uncouth, deformed and dirty body. In this way, women in ghost films are anti-teleological in form, resistant to the totalisation of the dominant ideology, and they place themselves against the ‘Desire of the Other.’ And hence, these women are pictured as physically abjectified. In Manichithrathazhu, the physically abjectified Ganga, but not a fully abjectified ghost, breaks the rules and codes of the patriarchal society of the Madambi palace, and hence, she becomes the ‘Other’ of the dominant ideology, and here , it is the male- centred society. She is visualized as hysteric with bizarre sound like a ghost, and daunts all the members of the family. Here Ganga, by becoming Nagavalli gets the power to frighten and defy the dominant ideology, and she does what the ideology forbids – entering the haunted room. Hysteric Ganga or Ganga haunted by Nagavalli rebuffs her recognition of former sexuality given to her by the patriarchal ideology with her metaphysics of presence. But the dominant ideology suppresses all its fear of the ghost of Nagavalli or fear of woman who goes beyond the Symbolic, by inducing her to accept the recognition of her former submissive sexuality. The abjectified body and mind of Ganga is come down to reality, and she is taught that she is the old Ganga who is submissive to the totalizing pattern of the system. She is made to ‘desire’ what she is ‘supposed to desire’ by the ‘Other.’

In order to evoke fear and loathe, ghosts are simulated and abjectified. This abject is what Bakhtin terms as ‘grotesque’ in which a bodily part comes to be too expressive. Eyes which bulge are grotesque, because the grotesque is looking for that which protrudes from the body, all that seek to go out beyond the body’s confines. Hence, ghosts are women who are grotesque creatures whose bodies transcend our preconceived notions of the female body. It is obvious in films like Meghasandesham and Sreekrishnaparunthu, in which ghosts appear as most grotesque with pointed fangs and uncouth, deformed and dirty body. In this way, women in ghost films are anti-teleological in form, resistant to the totalisation of the dominant ideology, and they place themselves against the ‘Desire of the Other.’ And hence, these women are pictured as physically abjectified. In Manichithrathazhu, the physically abjectified Ganga, but not a fully abjectified ghost, breaks the rules and codes of the patriarchal society of the Madambi palace, and hence, she becomes the ‘Other’ of the dominant ideology, and here , it is the male- centred society. She is visualized as hysteric with bizarre sound like a ghost, and daunts all the members of the family. Here Ganga, by becoming Nagavalli gets the power to frighten and defy the dominant ideology, and she does what the ideology forbids – entering the haunted room. Hysteric Ganga or Ganga haunted by Nagavalli rebuffs her recognition of former sexuality given to her by the patriarchal ideology with her metaphysics of presence. But the dominant ideology suppresses all its fear of the ghost of Nagavalli or fear of woman who goes beyond the Symbolic, by inducing her to accept the recognition of her former submissive sexuality. The abjectified body and mind of Ganga is come down to reality, and she is taught that she is the old Ganga who is submissive to the totalizing pattern of the system. She is made to ‘desire’ what she is ‘supposed to desire’ by the ‘Other.’

The so called ghost-haunted women are shown as frightening and aggressive, and these aggressive women are balanced as sexy, ie emphasizing their body and costume(mostly white saris) and vamping behaviour, and in this way, the ‘feminine’ side gets represented. The aggression that these women show can be termed as ‘hostile aggression’ which is explained as a type of aggression through which the subject derives some pleasure by inflicting harm. Daunting the system with extreme fear, women in ghost films experience immense pleasure. Thus, woman, constructed as the abject, is made a synonym of fear and disorder that is to be eliminated from the system.

The eye of the camera also makes woman an object of fear, and identifying with or looking through camera’s point of view, the onlooker also fears and starts loathing the aggressive and gruesome woman on the screen, and they identify with the dominant ideology that the film represents, for only it could ruin the ‘Other’. Hence, the success of the dominant ideology becomes the solace of the audience from the shattering fear.

This mode of ‘abjectification’ and mythification of woman as violent, sexy, evil and fatal is the subtle politics that deftly works on all through the ghost films. This discourse of the abject divests the sign woman of its denotative meaning, a human being or person with the potential for bearing children, and replaces it with connotative meanings such as woman as ‘Other’ or object of male desire and fear. Hence, it is true to say that, in ghost films, the dominant ideology interpellates or ideologically positions woman as a mere performing piece of unreal feminity. The eye of the camera or the patriarchal discourse strips woman off all her natural characteristics, and makes her an unnatural taboo, an abject, essentially exterminated.

This mode of ‘abjectification’ and mythification of woman as violent, sexy, evil and fatal is the subtle politics that deftly works on all through the ghost films. This discourse of the abject divests the sign woman of its denotative meaning, a human being or person with the potential for bearing children, and replaces it with connotative meanings such as woman as ‘Other’ or object of male desire and fear. Hence, it is true to say that, in ghost films, the dominant ideology interpellates or ideologically positions woman as a mere performing piece of unreal feminity. The eye of the camera or the patriarchal discourse strips woman off all her natural characteristics, and makes her an unnatural taboo, an abject, essentially exterminated.

Bibliography

Barthes, Roland. Mythologies. Trans. Annette Lavers. London: Jonathan

Cape, 1972.

Kristeva, Julia. Powers of Horror: An Essay on Abjection.

Trans. Leon S. Roudiez. New York: CUP, 1982.

Vice, Sue. Introducing Bakhtin. New York: MUP, 1997.

Niyas S.M.

Research Scholar

Institute of English

University of Kerala (Palayam Campus)

Thiruvananthapuram

niyas,

you are right here as the process of exorcism in itself is a male dominated process with latent sexual subjugation working as the main theme. manichitrathazhu is a different case as it attempts to identify the condition from a clinical perspective much more than the other two movies. So we should ideally give a better rating for it, despite the fact that it too succumbs ultimately to the dominant logic!

The eye of the camera also makes woman an object of fear, and identifying with or looking through camera’s point of view, the onlooker also fears and starts loathing the aggressive and gruesome woman on the screen, and they identify with the dominant ideology that the film represents, for only it could ruin the ‘Other’…..

This mode of ‘abjectification’ and mythification of woman as violent, sexy, evil and fatal is the subtle politics that deftly works on all through the ghost films….

thanks Niyas, for ur clear statement…

സുഹൃത്തെ ,എന്തിനേറെ പറയണം..കാടിളക്കി വരുന്ന കൊടുങ്കാറ്റിനും,ചുഴലിക്കാറ്റിനും,പെമാരികള്ക്കും,മാരാവ്യാധികള്ക്കും സ്ത്രീ നാമങ്ങളല്ലേ നമുക്ക് നല്കാനുള്ളത്…

really it s a thought provoking project..

That is a really excellent read for me, Must admit that you simply are one among the most useful bloggers I ever saw.Thanks for posting this informative article.

this is really a thought provoking article and also helps us to think in a different way about the ideology behind the representation of women in malayalam films..

this type of articles are a blow to those who think women can only be like this like in a new malayalam film in which an actor says to the heroine than “ne verum pennanu”. This concept of women especially OF MALAYALI WOMEN must be changed that assuming her of Sita or Savithri..